On a scale of 1-10, how true do the following 3 statements feel?

‘I am a mistake’

‘I am defective’

‘I am unworthy of being loved’

Any score above 8 starts to indicate the problem of shame. Though to be fair, people who are disproportionately ashamed of who they are would have probably wanted to award themselves a thousand more.

“Shame is a way of life here. It’s stocked in the vending machines, stuck like gum under the desks, spoken in the morning devotionals. She knows now that there’s a bit of it in her.”

- Casey McQuiston

What is Shame?

In shame, the focus of attention is on the “bad” self. Shame is a family of unpleasant self-conscious emotions that include embarrassment, guilt and humiliation, which makes us feel awful about ourselves.

Imagine tripping down the stairs and falling face-first onto the ground in a shopping center. Why was your initial thought ‘Did anyone see that?’ instead of tending to your agonizing physical pain first?

Shame is always present in our lives. We are motivated to maintain and achieve a positive sense of ourselves.

The issue with shame comes with a tendency to hide these negative emotions. Who likes to openly humiliate themselves? This makes it hard to recognize shame when it happens. For example, adolescents may superficially laugh off a poor exam result together while privately experiencing tremendous feelings of anxiety about failure.

As we avoid talking about our feelings of shame, we continue to have a lack of understanding about it.

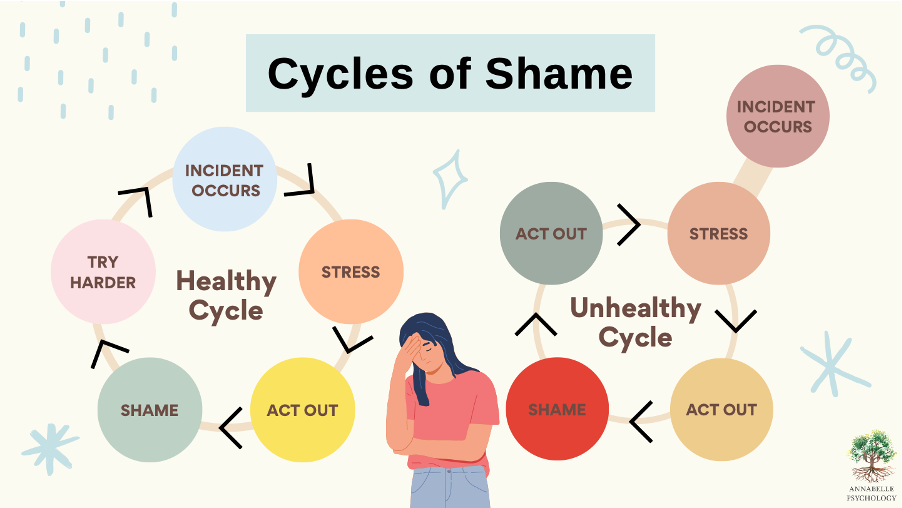

Comparing the Cycles of Shame: Healthy vs Unhealthy

Let us work together to understand the diagram of a typical circumstance for a healthy shame cycle (see diagram on the left). Imagine being called out or reprimanded in a group chat by your manager for a serious error you made at work. You start to feel psychologically stressed as your heart begins to beat faster, your palms sweat, and your cheeks flush with embarrassment. You feel ashamed of your mistakes as you worry about being judged poorly by your coworkers. To alleviate these unpleasant emotions of shame, you are driven to strive more in the future to avoid repeating the same mistake.

Unfortunately, this is not the case for those who struggle with shame (see diagram on the right). Replaying the same event above, instead of trying harder to lessen the feelings of shame, you find yourself in an unhealthy spiral. By having excessive self-critical thoughts, or even indulging in self-destructive behaviours, you inadvertently feed these shameful emotions. You begin to mistakenly ascribe your mistake to a dispositional problem that only arises due to your lack of skill, causing you to get stressed once again.

It is essential to deal with the unhealthy shame cycle as excessive feelings of shame can lead to serious mental health problems. Some of the negative consequences of toxic shame include:

Fear of letting people in

Excessively pushing people away

Feelings of embarrassment and/or humiliation

Low self-esteem

Lack of empathy for others

Cynical thoughts about the future (e.g., believing that bad things happen to bad people)

Obsessive rumination on self-critical thoughts (e.g., ‘I am unworthy of being loved’)

Self-destructive/Addictive behaviours (e.g., substance use, self-harm and suicide)

Overcoming Shame

One way to overcome the problem of shame is from an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) approach. ACT is a psychological intervention that involves accepting and embracing life events as they are without seeking to change them. It also involves committing to making meaningful steps to improve and enhance your life.

Before we dive deeper into ACT, we need to first understand how an unhealthy shame cycle forms and takes root.

As you get older, you start to develop a better understanding of how your actions affect others through learning from your mistakes. Parents hold an important responsibility to remind you that mistakes are normal. We can use the lessons we have learned from our failures to make better decisions in the future.

However, instead of guiding children through their mistakes, parents may unintentionally send unhelpful messages to the child. They may do so by expressing criticism and/or disappointment directed at the child rather than their conduct:

“Can you stop being the laziest child in the house and do some chores?”

“You just had to be the only student in class to fail that test.”

“Stop embarrassing me and behave yourself.”

This may give the child the false idea that he or she is undeserving of affection, which can lead to shame. Unhealthy shame thus prevents a more positive perspective of oneself, making it difficult for the child to develop a healthy sense of self-worth.

Let’s now look at how the ACT’s 6 key processes can help you overcome shame:

(1) Acceptance

When we are overwhelmed with unwanted feelings of shame, it is instinctive for us to try to avoid and suppress them. Acceptance, on the other hand, is acknowledging and embracing the portion of yourself that feels “not good enough”, “unlovable” and/or “rejected”.

Do not get us wrong, acceptance does not mean that you are inviting or seeking feelings of shame. After all, who likes to dwell in their misery? Acceptance simply makes room to experience the agony of shameful emotions.

Soon, you will quickly notice that you are less disturbed by these feelings of shame if you do not attempt to escape from them. Isn’t it funny? The more you want to embrace and accept your shame, the less salient they become.

(2) Cognitive Defusion

“I am unlovable at home.” “I am not good enough at my workplace.”

These are some common self-criticizing thoughts from someone struggling with shame. Cognitive defusion involves establishing a psychological distance from these self-defeating beliefs, understanding that they are just one of many non-threatening perspectives.

To do so, start by asking yourself this question: Who will have control over your life – you or your mind? Choosing a different relationship with your problematic thoughts allows you to take a step back and not be consumed by them.

For instance, you can recognize a mistake you made at work as it is without attributing them as part of your personality.

(3) Being Present

Take a trip back home from work or school with me. What do you usually do on the train/bus/walk back home? Are you consumed by social media on your phone? Or maybe you are planning ahead of time on how you are going to rest at home? Notice how none of these options include spending intentional time in the present.

Being in contact with the present moment is also known as “being in the now”. It involves focusing on what is happening to you, and/or in your environment at the present moment rather than on what has happened in the past or what may happen in the future.

When you are faced with feelings of shame, fully embrace them first! Then, acknowledge that past events are irreversible. Although you could have responded better, understand that you cannot change the past. Making mistakes is what makes us human!

When you start to focus more on the present, you spend less time evaluating and criticizing yourself and others.

(4) The Observing Self

If we are being honest, we sometimes feel ashamed of ourselves in certain situations because we project our worries or past experiences onto the current situation. However, we fail to see that most of these assumptions are irrational and therefore our interpretation of such occurrences is often incorrect.

Hence, the next phase is observing and knowing yourself as part of a context. Think of this phase as objectively looking at your situation from an observer’s point of view. Refrain from allowing your thoughts and feelings to cloud your judgment on the situation.

This is realizing that your thoughts and feelings are a result of the situation, not of your personality. You can experience feelings of shame but you are NOT defined by them!

(5) Values – What matters to you?

Whether you recognize them or not, everyone has values. Values are qualities that you believe are the most important. They determine your priorities, guide your personal growth and help you make decisions about how you want to live your life.

The issue with our values is that we are not constantly in touch with them. When life gets in the way, we might lose track of them and become unsure of what they are. This causes our values to become more vulnerable and susceptible to change.

What used to be unimportant to you such as fear of judgment or embarrassment could have unconsciously become your most important value over time.

Hence, we encourage you to take some time to consider:

1) What are the things that are most important to you?

2) How would you like to be remembered?

3) What are the things you strongly object to?

Our values need to be sorted out first before we can come up with a plan to challenge your feelings of shame.

(6) Taking Committed Actions

Now that you have learned to embrace the unwanted feelings of shame and developed a clearer sense of values you wish to live by, we have now come to the final step of overcoming shame – taking committed actions. This is where you take concrete actions and behave in ways that lead to positive changes in your life.

There are many ways you can do this depending on what you are struggling with. For instance, you can set goals that are in line with your values and beliefs. You could even intentionally expose yourself to difficult thoughts or experiences.

Consistently practice and commit to those behaviours to achieve the goals that you have set out. The key to taking committed actions is to incorporate changes in your life that will align with your established values.

A Final Piece of Advice

We should stress that every human being is radically imperfect and broken in their own way. It’s okay to accept your flaws as everyone has them. Remind yourself that no one is perfect! If you feel comfortable enough, find a friend whom you trust and share your feelings of shame with them. We are positive that they will be more than happy to listen to your struggles!